Feature: Diving Deep

A new documentary about her late husband, deep water explorer Mike deGruy, has helped Mimi Armstrong deGruy ’75 process his loss while also carrying on his important work.

Jana F. Brown

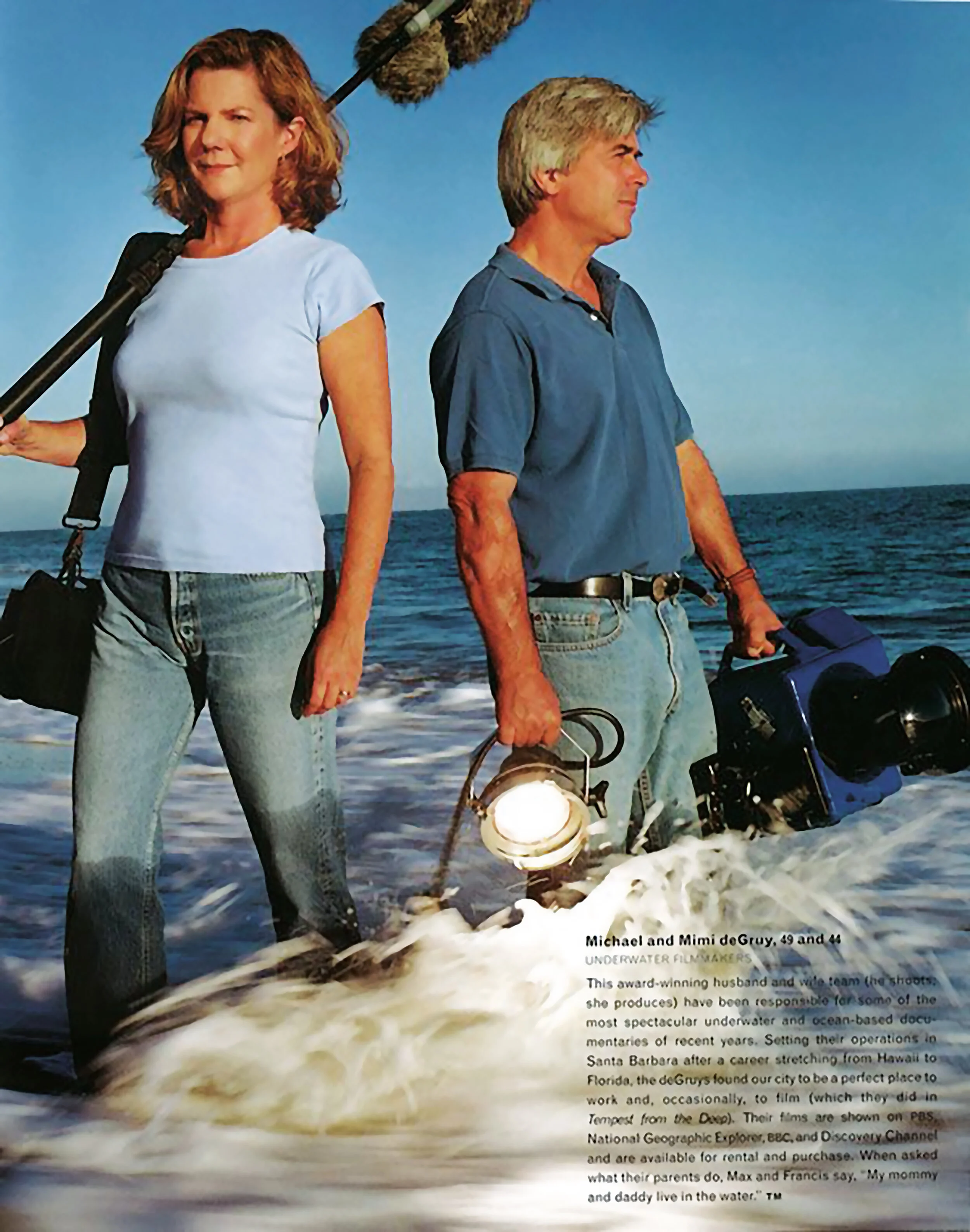

Mimi deGruy ‘75 and her husband, Mike, cameras in hand, in the surf near their home in Santa Barbara, Calif.

At the urging of her husband, and in the interest of filmmaking and research (and love), Mimi Armstrong deGruy ’75 learned to scuba dive. And not only did she dive, but she swam with sharks, whose reputation as man-eaters preceded them. Up close, deGruy (pronounced “degree”) came to appreciate the intricate way the females lay eggs and carefully wrap them into the substrate of the ocean to protect their budding young.

Mimi and Mike overlooking the Sea of Cortez, on the lookout for stingrays – relatives of sharks – for one of their documentaries.

“I knew I didn’t want to be a producer who stood on the sidelines,” says deGruy of the 1990 film produced by National Geographic called Shark Encounters (the BBC version went by Sharks on Their Best Behavior). “The whole point of our film was to point out how sharks defy the stereotype of a man-eating predator. Anyone who has spent time in the ocean realizes how fragile it all is and what an important role sharks, as apex predators, play in the health of the ocean.”

The project was conceived as a first-person narrative of someone who had been attacked by a shark, but remained undeterred by the potential danger of returning to the water. That person was Mimi’s husband, underwater explorer and cinematographer Mike deGruy. In 1978, Mike had been attacked by a grey reef shark in a lagoon near Enewetak Atoll off the Marshall Islands in the western Pacific Ocean. Despite suffering grave injuries to his right arm, he survived. That’s the kind of guy Mike was, someone determined not to set limits, even recreating the attack years later (surrounded by protective gear) in defense of the shark’s behavior.

Mimi referred to Mike as an “emissary of the sea” and was immediately drawn to his adventurous spirit. He possessed a rare brand of enthusiasm not easily quantifiable in words, and encouraged in his wife the same zest for the ocean and its inhabitants. The two became partners in filmmaking and in life, marrying in 1989 and eventually settling in Santa Barbara, Calif. “I did get in the water with sharks,” Mimi says of her initial work with Mike. “Mike was very determined. What I found compelling was the diversity of sharks. We need diversity to survive, and sharks are an elegant example of that. That [1990] film woke me up to the importance of maintaining the ocean world.”

Over two decades, Mimi and Mike worked together on multiple film and television projects, including episodes of Portrait of America (where they met), The Search for Ancient Americans, The Infinite Voyage, and National Geographic Explorer and longer documentaries that included the aforementioned Shark Encounters, Tempest from the Deep, Incredible Suckers (about cephalopods), and The Octopus Show. Deepwater Rising, which explores threats to the marine environment of the Gulf of Mexico, was in production when Mike died. It was the fall of 2012 when Mimi deGruy found herself again faced with a choice involving risk. For many long hours, she sat in a room observing her husband on a screen, watching as he made unprecedented discoveries in the depths of the ocean and shared his findings with unbounded joy. By the time Mimi began working in earnest on Diving Deep: The Life and Times of Mike deGruy (divingdeepmovie.com), her husband had been gone for months, the victim of a helicopter accident on February 4, 2012, while working with Titanic director James Cameron on his Deepsea Challenge exploration in Australia.

“It was a very slow process,” Mimi admits now, as she thinks back to her work in those initial days compiling footage for the documentary. “It took me a very long time to go through it all. I could only spend a few hours – if that – a day. It was just too hard and I had hours and hours of material.” Making a film for the first time without her partner felt daunting at first, but Mimi was determined not only to tell Mike’s personal story, but also to share his amazement at his ocean findings and continue his advocacy for environmental protections. Mimi deGruy did not set out to become a filmmaker. She came to St. Paul’s from Pittsburgh, Pa., succeeding her father, Henry Armstrong ’49, at the School. A degree in art history followed from Yale as did a job at CNN in Atlanta and a position in the documentary unit at Turner Broadcasting. Her path converged with Mike deGruy’s when Mimi was working on a 1986 project that required an underwater cameraman. Seeing Mike in his element, filming the creatures that made up the marine ecosystem of American Samoa, had Mimi – by her own admission – “totally smitten by how comfortable he was in the ocean.”

After a couple years of long-distance dating, Mimi and Mike moved together to Los Angeles, where they got the commission from the BBC to produce the film on shark behavior. Mike talked her into diving with the Chondrichthyes a mere two weeks after Mimi earned her scuba certification. The couple spent the next three years observing shark habits and traveling the world. “What was interesting for me about that film when I look at our partnership,” Mimi says, “is that he was a marine scientist and I was a big-picture person who could take a broad view of how the average Joe might respond to a marine story. He would tell me something incredible and think it was something everyone knew – and I would tell him that was not true.”

Mimi behind the camera, on one of her personally infrequent – but successful – underwater shoots.

In Diving Deep, Mimi has captured the larger-than-life persona of her husband, as he is ensconced in an oversized (bright yellow) underwater “space suit,” declaring – a la Buzz Lightyear – “to infinity and beyond;” as he marvels at the curious, electric creatures of the deep while piloting submersibles; as he dives under the ice through a seal hole in the Antarctic; and as he disguises himself as an elephant seal pup to capture the predatory behavior of killer whales in Patagonia or as a floating iceberg to observe otters in Alaska. In his career as an explorer and filmmaker, Mike became a recognizable host of many specials on Discovery Channel’s famed Shark Week and teamed up for multiple projects with David Attenborough and James Cameron. With Cameron, Mike served as underwater director of photography for the 2005 Discovery Channel special Last Mysteries of the Titanic, which live broadcast dives into the bowels of the doomed ship.

Described in Diving Deep by several who knew him well as stubborn, Mike was forever holding himself, his colleagues, and his equipment to the highest standards. His work piloting deep rovers to travel up to 15,000 feet under the sea is described as “a final frontier opportunity” akin to space exploration. In her 80-minute documentary, Mimi has shared her husband’s breathtaking underwater images of creatures never before seen that make one question the very circle of life – all through Mike’s boundless sense of awe. “Mike was incredibly curious and had a certain daring,” Mimi says. “He loved to be the first to get this or that behavior or phenomenon and he really loved exploring and sharing his own sense of joy with everyone.”

According to his biography at mikedegruy.com, Mike “has dived under the ice at both poles, been to all continents, become a submersible pilot, dived hundreds of times in many types of submersibles, filmed the hydrothermal vents in both the Atlantic and the Pacific, and had more meals on the Titanic, now resting at 12,500 feet deep, than did the doomed passengers.” He did it all with the spirit and sense of wonder of a child and with a signature smile and laugh to punctuate it. His sudden and surprising loss – in an air accident rather than a diving incident – reverberated far and wide. “He was somebody who was lit from within,” says Mimi. “He just had this joy and wonder that really was contagious. People felt it and he could inspire them to action. The flip side is that he was intensely stubborn and very sure of what he believed. He was also very kind and loved everyone. He had that ability to make you feel like you were the most important person in the room.”

In the final two years of his life, Mike was consumed by the disastrous impact the Deepwater Horizon oil spill was having on the ecosystems of the Gulf of Mexico. The damage hit close to home, as Mike had grown up in Mobile, Ala., learning to swim, explore, and dive in the waterways that fed the Gulf. In her grief, Mimi began sorting through countless hours of tape, first as a catharsis, when she came across previously unseen footage of an agitated Mike ranting about the damage to his beloved home waters. As he paces back and forth and waves his hands (hands were his second language, according to Cameron) he laments the lack of government action and expertise in cleaning up the mess. “I started watching footage and it was almost like Mike came alive,” Mimi says in Diving Deep. “His whole life led him to this moment of outrage.”

The deGruys near their home in Santa Barbara, Calif.

Feeling that the message of the Gulf disaster was a powerful instigator for environmental awareness (particularly of the dangers of chemical dispersants used to break up oil spills that only end up expanding their reach), Mimi was compelled to make a film. She approached Diving Deep as a character study featuring Mike and his bliss for marine habitats, and building to his arrival at outrage. In its review of the film, the Hollywood Reporter said, “The doc makes us understand how deeply disturbing this was to a man who always savored the wonders of the unpolluted natural world.”

“Making the film was an exercise in telling Mike’s story,” Mimi says, “but it was also trying to understand my relationship with him – the parallels of how we approach death and dying and how we look at the natural world. We deny ourselves the ability to think about death and what we are doing to the natural world. In both cases, everything can change in a moment.” While she admits it was challenging at times making her first film without Mike, Mimi also describes it as liberating, gratifying, and as a rekindling of her love for the filmmaking process. Watching the footage of Mike was a gift, she adds, both to her and their children, Frances and Max.

“To be able to spend that time with Mike allowed me to continue the conversation with him beyond his death,” she says. “It gave me something bigger than my own personal sadness; to look at how we are not spending enough time exploring oceans. It threw me a life ring.” Diving Deep has been well received in its initial film festival tour. It was featured as the opening night film at the 2019 Santa Barbara International Film Festival; earned the Audience Award for Best Documentary Feature and the Spirit Award from BZN International Film Festival in Bozeman, Mont.; was voted Audience Favorite at the Aspen Mountain Film Festival in Colorado; and was a Special Jury Nominee at the 2019 Jackson Wild Summit. While honoring her husband (“Mike would probably be a little embarrassed and proud of me that I did it and got it out there.”) and sharing some of his stunning underwater cinematography, Mimi also has created a film with a mission of inspiring awareness and action for marine environments. She is proud that the Hollywood Reporter called Diving Deep “an understated but effective environmental manifesto” that “serves as a kind of elegy for a pristine, mysterious underwater kingdom that may never be recovered.”

“I can’t quantify the effects of this film,” Mimi says. “What I am most motivated to do is use this film to encourage people to get engaged. Mike said to look in our backyard, in the mirror, in our hearts for what we can do differently. The most important thing is get out there and vote with the ocean in mind. If I can use this film to encourage people to do that, I’ll be very happy.”